An appreciation of the importance of the ordinary, the everyday in our lives has a long history in art. It dates back at least as far as the early 18th Century in France with artist Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin and his painting “A Lady Taking Tea” from 1735. The setting is unpretentious, modest even and there is an air of calm self-absorption in the scene. The skill of the artist is in transforming an ordinary occasion with simple furnishings into something almost seductive.

Chardin, A Lady Taking Tea, 1735, oil on canvas, 81 x 99 cm

Author Alain De Botton argues that given the way the world is going, we need all the reliable, unassuming and inexpensive satisfactions we can get. He believes that it lies in the power of art to honour the elusive but real value of ordinary life.

This may have been the motivation behind the art of Isabel Quintanilla (1938 – 2017). In Spain, the practice of granting a special reverence to ordinary everyday objects dates back even further to the Baroque masters such as Velazquez and his ‘bodegones’; that is, art depicting pantry items, game, food and drink. Quintanilla was a member of the Madrid School of realists who graduated from the Academia de San Fernando, where rigorous training in the traditional academic manner had been upheld since the 18th Century.

Quintanilla, Cabracho (Scorpionfish), 1992, oil on canvas, 70 x 90 cm

Like other pupils of the time, including Antonio Lopez Garcia who is arguably the most famous of the Madrid realists, she had to develop her skills against the backdrop of the intellectual and artistic repression of the middle years of Franco’s dictatorship.

While some may regard the art of the Madrid realists as minimalism, what makes them unique is their ability to “de-nude, de-code and explicate the essence of our collective consciousness”. What we are viewing is the object itself, free of any socio/political contexts. The subject matter of Quintanilla’s work ranges from simple still life to panoramic landscapes.

Quintanilla, Glass On Top Of A Fridge, 1972, pencil on paper, 48 x 36 cm

Viewing work like this is very instructive to me. Occasionally I get sucked into producing grandiose scenes forgetting that some of the simplest compositions can make the best paintings - if the artist has the skill. Perhaps it’s a matter of being in the moment, focusing on the object itself free of any distractions.

In his review of a 1996 exhibition of Spanish Contemporary Realists held in London, Edward J Sullivan writes of the absolute immediacy and intensity of their vision. But he also argues that it’s important not to draw to close a link between their work and that of the Baroque masters of the past. Artists such as Velazquez were operating largely under the strict guidelines laid down by the Catholic Church and the counter reformation.

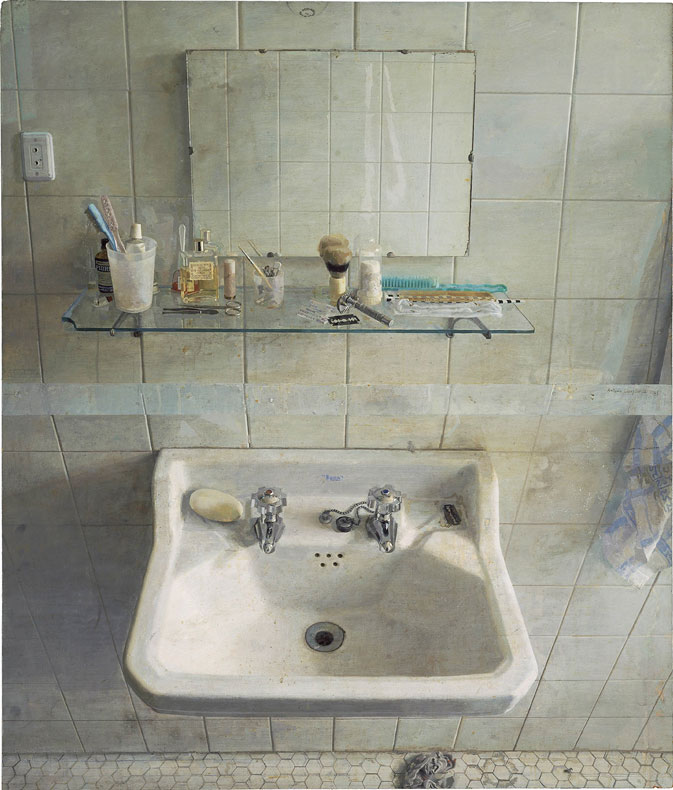

Quintanilla, El Telefono, 1996, oil on board, 110 x 100 cm

Unfortunately, whether I scanned this image from a catalogue, or downloaded it off the net, I am unable to convey the absolute clarity of the vision in this work. This is beyond photorealism and I think it’s because of the use of light. There is an intimacy in this scene that would seem to run contrary to the cold, clinical hard-edged nature of much photo-realist art. You get the sense that you are entering someone’s private world.

Quintanilla, Vendana (Window), 1970, oil on board, 131 x 100 cm

Views through windows have been a popular topic for artists for centuries. What fascinates me is the suggestion of furniture in the bottom left of the composition. There is also the cool, clear light and a sense of imprisonment in the scene.

Quintanilla had exhibited either individually or in group shows at the Prado in Madrid, the Marlborough Gallery in London and at many other venues. Her work forms part of the collections at the Baltimore Museum of Art, the Smithsonian Institute in Washington DC and in various galleries throughout Europe.

References;

Books;

“Contemporary Spanish Realists”, 1996, Marlborough Fine Art, London

“Art As Therapy”, 2014, Alain De Botton & John Armstrong

The Net;

Leandro Navarro Gallery